John + Gena: dynamite on screen and off by Matthew Thrift

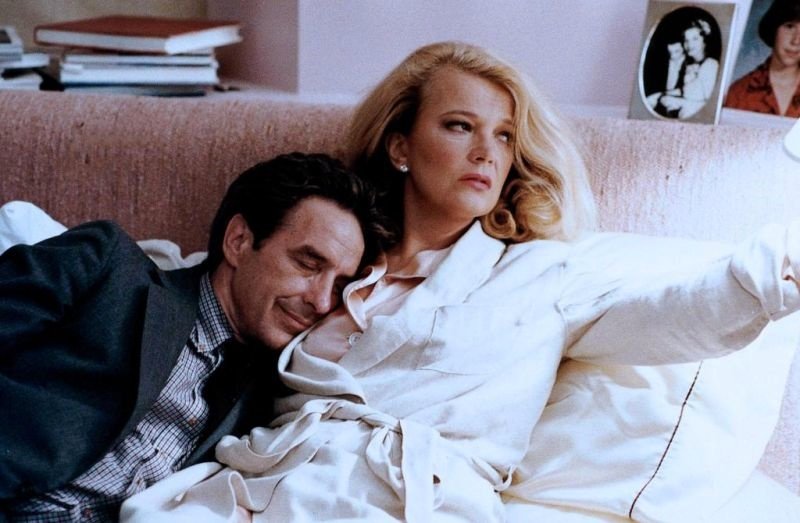

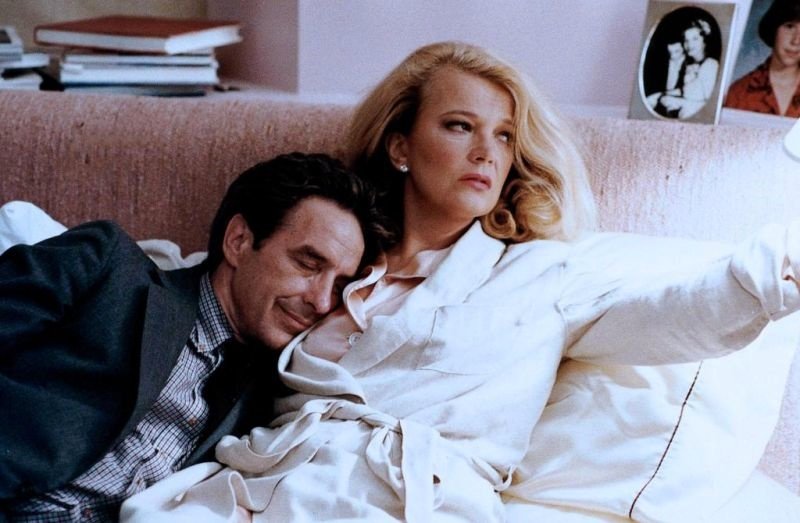

Fiery and tempestuous, but devoted to their filmmaking, director John Cassavetes and actor Gena Rowlands are one of cinema’s great husband-wife partnerships, producing a string of collaborations of startling psychological intensity.

Before I met Gena, I was a bachelor going out and torturing people. I think that’s good for young people. When I saw her, that was it! The first time I saw her, I was with an actor, John Ericson, and I said, ‘That’s the girl I’m going to marry!’

Both attendees of the American Academy of Dramatic Art, but separated by a year in age, it wouldn’t be until they were a couple of years out of school that John Cassavetes began his ruthless pursuit of Gena Rowlands. The couple were like chalk and cheese; he a jealous romantic, she ferociously protective of her independence. The arguments were ground-shaking from the get-go, and would only escalate from there.

But theirs was a personal and professional relationship which lasted until Cassavetes’ death in 1989. As both their careers began to develop (hers as an actress, his as both an actor and, starting with his directorial debut Shadows (1959), as the founding father of American independent cinema), Gena became as much Cassavetes’ muse as she did his wife, each of them doing their best work when in each other’s tempestuous company.

I don’t think you can do serious work in television… I wanted to do other things, and there was a certain amount of opposition to this. It came down to the fact that they didn’t know me and I didn’t know them well enough.

After a series of re-shoots for Shadows left him $30,000 in debt, Cassavetes was in desperate need of some income if he was ever going to fund the film’s editing and 35mm blow-up costs. With Rowlands having extracted herself from a relatively lucrative contract with MGM on discovering she was pregnant with the couple’s first child, and Cassavetes having had few acting opportunities during the protracted production period of his first feature, the couple were in dire financial straits.

When the offer from a Universal executive came in to play Johnny Staccato, ‘television’s jazz detective’, the brunt of Cassavetes’ ego’s song-and-dance routine was saved for Gena: “Can you imagine that son of a bitch wants me to do a television series? What the hell do you think I’ve been working for? I’m an artist! I don’t do television series! What kind of crap is that? Go out and do something for the sponsor of deodorants? Am I insane?”

Of course, he had little choice but to accept. Despite directing five of the more interesting episodes in the widely syndicated series (and getting to work with Rowlands on one, the unremarkable ‘Fly Baby Fly’), Cassavetes quickly tired of the artistic constraints imposed by network television, publicly denigrating the show and attacking the sponsors in the hope of being fired. Or as he himself put it, “I went to New York and took pictures with child molesters then called their agent”.

Making A Child Is Waiting was like drowning painlessly. It was a slow death. Shadows kept haunting me all the time I was trying to make like this big Hollywood director… I’ve since learned I’m just not temperamentally suited to that kind of ball game… It’s hard to be on the outside, and yet that’s really where you want to be.

Cassavetes’ first opportunity to direct his wife on screen came with a project inherited from director-producer Stanley Kramer. It would be his first real stab at making a studio picture as director-for-hire, having dipped his toe the previous year with the more personally resonant (but likewise inherited) feature, Too Late Blues (1961).

His experience on A Child Is Waiting was an unmitigated disaster from day one. Cassavetes clashed with just about everyone involved, taking pleasure in winding up screenwriter Abby Mann (who hung around the set to ensure the director didn’t change a word of his dialogue) and provoking his anxious and volatile star, Judy Garland. When both Cassavetes and Garland had to be physically restrained during a particularly frenzied bout of disagreement, Burt Lancaster stepped in to take his co-star’s side against the filmmaker.

With Rowlands in only a minor role, he had no real allies left, the last straw coming during post-production. For him, the primary focus of the picture had always been the children at the heart of the story, not the adult leads. Stanley Kramer saw things differently. When Cassavetes attended the first screening of the film for the executives at MGM, he discovered that Kramer had completely re-edited it behind his back to amplify the sentimentality. “Take my name off the picture”, said Cassavetes as he stormed out of the screening room. Then he smacked Kramer in the mouth for good measure. For the time being, the director’s Hollywood career was over.

When I decided to write and shoot it, I came home and said to Gena, ‘Are you willing to go without all the luxuries for the next couple of years so we can put everything we’ve got into the picture?’ She said, ‘Yes – except for getting my hair done. I insist on that!’

With his bridges burned at the major studios, there was no way that Cassavetes was going to find traditional funding for what would become Faces. If Shadows was a rough-and-ready exercise in filmmaking on the run, a young filmmaker’s film about youth itself, then Faces would be the first to define Cassavetes’ mature style, an examination of love, middle age and the politics of male-female communication that would extend into his next feature, Husbands (1970) and beyond.

Using his salary from a short-lived day job at Screen Gems (coming up with ideas for new TV shows that were never commissioned) and the fee from an unproduced script he wrote for Don Siegel, Cassavetes moved ahead with the unheard-of-at-the-time idea of an entirely self-financed production. Favours were called in at every opportunity, from the use of friends’ and family’s homes for locations to the use of Haskell Wexler’s camera. A young Steven Spielberg worked as an unpaid runner, while the milkman was given a promise of the share in any profits when Cassavetes couldn’t afford to pay his bill.

Refusing to work to any form of schedule or budget, Cassavetes let the production evolve organically, giving his company of actors whatever time they needed to find their way into character, shutting production down whenever rewrites or extra rehearsals were required. Rowlands would give the first of six extraordinary performances in her husband’s work, despite later describing the shoot as the most difficult she’d ever undertaken. With Rowlands pregnant at the time with daughter Xan, Cassavetes’ insistence on goading her through multiple takes took its toll and tensions between the two ran high.

Finally printing over 115 hours of 16mm stock (paid for through several remortgages of his and Rowlands’ home), Cassavetes would spend 30 months in post-production, shaping the film into what would ultimately become the director’s first masterpiece.

Directing is really a full-time hobby with me. I consider myself an amateur filmmaker and a professional actor. I’m a professional actor out of defence. I’d prefer to be an amateur actor. But I’ve got to have money to make films. Unfortunately, it’s an extremely expensive hobby.

Despite his protestations of professionalism as an actor, Cassavetes could prove as tricky a customer for those directing him as he could for those he directed in his own projects. More often than not, disagreements were borne out of the actor’s strong-mindedness rather than outright contempt (although Roman Polanski, who directed him in Rosemary’s Baby, may beg to differ), but one need only watch a few of his actor-for-hire roles to witness varying levels of engagement.

One thing on which Cassavetes could always be relied however, was convincing producers to hire his actor pals alongside him. Offering an atypical role for Peter Falk and a film-stealing one for Rowlands (as well as minor parts for Faces’ Val Avery and Jack Ackerman), Machine Gun McCain proves a lean, energetic slice of genre filmmaking from Italian director Giuliano Montaldo. Never one to miss an opportunity, Cassavetes’ greatest coup surfaced over dinner one night with the film’s producer, an Italian millionaire by the name of Count Ascanio Bino Cicogna. His fee for those weeks on Machine Gun McCain may have helped him finish editing Faces, but with wine and charm in plentiful supply that night, it was that dinner which got him his funding for Husbands.

To understand the story of Minnie and Moskowitz and the relationship of the title characters through their fights, arguments, pounding on doors, the torture, the pain, the screaming and the eventual marriage, it is essential for the audience to take itself back to when it cared. The romance takes place in a time before intellect.

An oft-overlooked gem in his filmography, Cassavetes took a cautious step back into studio filmmaking with Minnie and Moskowitz, taking advantage of Universal’s commitment to fund a series of low-budget features in the wake of the success of the likes of Easy Rider (1969). Racing through pre-production, he took a similar approach here as he did on Faces, filling the cast with friends and family members and taking over their homes to fulfil his location requirements.

With many aspects of the relationship between the protagonists mirroring his own with Rowlands, Cassavetes filled the screenplay with autobiographical references, and in casting his friend Seymour Cassel opposite his wife, ensured that the off-screen frictions that existed between the pair would colour their onscreen dynamics. He did everything he could to keep tensions high, sometimes marching a terrified Cassel into Rowlands’ bedroom when she was sound asleep to insist on an immediate rehearsal that he pretended Cassel was demanding. If this wasn’t enough to rile her up, he’d begin laying into her performance to create an exasperated energy she could carry with her into the scene. Always prepared to coax, trick and tease emotion out of his cast, the final interpretations always rested with the actors themselves, with the multiple takes upon which he insisted allowing him to shape the material to his liking at a later date.

If his tentative return to the studio fold with Minnie and Moskowitz led to a much less protracted pre-production process than usual, it wasn’t to last. Unhappy with the way the film was eventually marketed, Cassavetes gave a disastrous interview to Playboy magazine accusing the Universal executives of incompetence. Plans for a low budget, multi-picture deal that had been mooted until then instantly went up in smoke.

[Gena and I] were talking about how difficult love was and tough it could be to make a love story about two people who were completely different culturally, coming from two different family groups that were diametrically opposed and yet still regarded each other very highly… Gena and I are absolutely dissimilar in everything we think, do and feel. Beyond that, men and women are totally different. When I started writing the script, I kept these things in mind and didn’t want the love story easy. I made a lot of discoveries about my own life.

Considered by many to be his crowning achievement, Cassavetes conceived A Woman under the Influence as a gift for Gena. Unable to find funding for its initial life as a stage play, the start-up money was split with Peter Falk, who was insistent on playing the male lead. But it still wasn’t enough to move forward. Hoodwinking the American Film Institute into hiring him as a filmmaker-in-residence, Cassavetes gained access to all their equipment in return for leading some classes in filmmaking. What this effectively meant in practice was that Cassavetes now had a crew for the feature, made up of eager students (including cinematographer Caleb Deschanel), none of whom he’d need to pay.

Financial difficulties on the film were legion, but once again he refused to be dictated by anything resembling a schedule. If a scene took a week to shoot, so be it. Many cast members spoke of a familial atmosphere on the set during production, but more so than ever Cassavetes refused to make things easy for Gena. Rowlands gives one of the greatest screen performances in cinema (although she lost out on the Oscar to Ellen Burstyn in Alice Doesn’t Live Here Anymore), but Cassavetes’ direction (or often lack thereof) could be brutal. Knowing exactly how to push her buttons, his tactics could be seen as tantamount to psychological abuse; mocking, taunting and wearing her down to elicit reactions that could work for the character.

Casting her real-life mother to play that of her character’s proved another unbalancing device, an off-screen relationship Cassavetes wasn’t shy in attempting to manipulate for the needs of the film. Gena knew what he was doing, but it was only in retrospect that she was able to look back on the situation with any real sense of perspective: “John encouraged you to the point that you pushed yourself into areas you feared with other directors”. While Cassavetes would take greater stylistic leaps with Opening Night and Love Streams (1984), in many respects A Woman under the Influence remains his quintessential work, the apotheosis of his working relationship with his wife and muse.

The actor can’t deliver in this situation. Hollywood directors create this situation. They make it possible for the actor to give nothing.

A quickie acting gig for the couple which (financial benefits aside) offered thankless roles for both, Two-minute Warning was shot during the latter post-production stages of Cassavetes’ The Killing of a Chinese Bookie (1976). Helmed by veteran TV director Larry Peerce, it’s a ploddingly orchestrated affair that adheres to the then-popular disaster movie template, introducing a slew of one-dimensional characters only to have them picked off one by one by a motivationally-confused sniper at a football game.

Perhaps most surprising was Cassavetes’ willingness to share the screen with an awkwardly bewigged Charlton Heston, given the pair’s fractious history. Back when the Academy Award nominations were announced in 1969, Faces picked up three. Cassavetes received a call from Screen Actors’ Guild president Heston, threatening the director with expulsion from the Guild and a hefty lawsuit for not abiding by its salary or contract regulations during production. He’d contacted the filmmaker earlier to initially press the issue, insisting dues be paid from any eventual profits the film made. The furious Cassavetes’ response was typical. “Sue me” he said, refusing to attend the ceremony at which Faces went home empty-handed.

When I am the director and Gena is acting, disagreement is not a bad thing. It’s really interesting. You don’t want an actor who is always polite and serious. You need someone who gets angry. They call me at five in the morning to insult me and that’s normal… That’s what life is about – for living through problems and for sharing them, isn’t it?

Inspired by the likes of All about Eve (1950) and A Star Is Born (1954; the 1976 Barbara Streisand version of which he turned down the opportunity to direct with an alleged “Why would I want to direct you?”), Cassavetes’ backstage drama is his most female-centric work, literalising his career-long thematic concern with performance via an examination of age, insecurity and celebrity. While much of the screenplay evolved out of discussions with Rowlands, whose experiences with an often hysterical public after the release of A Woman under the Influence mirrored those of her character Myrtle, Cassavetes also drew on his time directing the manically insecure Judy Garland in A Child Is Waiting.

Writing and conceptualisation proved a lengthy process, with Rowlands and Cassavetes often in disagreement on the shape the film should take; Gena favouring clarity, Cassavetes ellipsis, but the biggest battles were over the way the film dealt with the subject of ageing: “I softened the ageing theme because it was all very, very painful and the people I care about were upset by it. I mean Gena. But it wasn’t just that. I didn’t want the film to be too destructive”.

It was also the most technically challenging directorial assignment Cassavetes had ever given himself. Not only did it have the biggest cast he’d worked with, but the demands of filling a large part of a 2,000 seat auditorium for the performance scenes with SAG-approved extras took a sizeable chunk out of his tight budget. Luckily, the acting job that required him to explode for Brian De Palma (The Fury, 1978) ran over-schedule, meaning an extra $10,000 towards production costs. It went little way to helping him settle actor Joan Blondell however, who struggled with what she saw as Cassavetes’ unique approach to directing.

The film opened disastrously in America, Cassavetes swiftly deciding to pull the film from cinemas. It would be a long time before Opening Night would receive its due as one of the filmmaker’s finest achievements, and further evidence of Gena Rowlands as the greatest actress of her generation.

So they sent [the script] to Columbia, and a couple of days later [my agent] called and said, ‘I have some good news and some bad news. One, they like the picture very much and want to buy it. And they want to have Gena in the picture.’ And I said what’s the bad news. ‘The bad news,’ he said, ‘is they want you to direct it.’ So that’s where we started.

Cassavetes had no intention of directing Gloria, a script he’d knocked out in a couple of weeks to sell to MGM. But with Gena attached and time to work on some rewrites before Columbia eventually took the script instead, the money finally proved too good to turn down. Rowlands was sold on the idea from the outset, keen to take on a tough-talking, leading role that in some ways resonated with her long-held love for Marlene Dietrich.

It was unlike anything Cassavetes had ever undertaken before: a $4m budget; a large, professional crew; a strictly enforced sequential shooting schedule and no final cut. While the production went by smoothly enough, Columbia sat on the film for almost a year, convinced it wouldn’t prove profitable enough to market. They weren’t wrong. Despite winning Gena the best actress award at the Venice Film Festival, the film did middling business. Not that Cassavetes really seemed to care: “It was television fare as a screenplay but handled by the actors to make it better. It’s an adult fairy-tale. I always thought I understood it. And I was bored because I knew the answer to that picture the minute we began”.

I read the script. To my mind, it had nothing to do with Shakespeare – it was an interesting plot. It was complicated. And I thought it was a comedy, but I wasn’t quite sure.

Cassavetes was right, Paul Mazurksy’s Tempest has very little to do with Shakespeare beyond its most obvious allusions. He can also be forgiven his curiosity as to the film’s tone, as even 30 years on it remains difficult to judge. It does, however, feature Raul Julia as a Greek shepherd playing ‘New York, New York’ on his clarinet to a herd of flying goats. So there is that.

While Rowlands is given little of substance with which to work, Cassavetes turns in a surprisingly nuanced performance that belies his difficulties with Mazursky. I say ‘his difficulties with Mazursky’, but it was really the reverse that was more often the case. Up to his old tricks, Cassavetes was demonstrably uncooperative throughout filming, often point blank refusing to do what his director asked, once again teasing Gena almost to breaking point. The film itself remains something of a chore, its laborious direction something even a fully committed turn from Cassavetes couldn’t have fixed

That’s all I’m interested in, love. And the lack of it. When it stops. And the pain that’s caused by loss or things taken away from us that we really need. So Love Streams is just… another picture in search of that grail… or whatever.

Loosely based on the 1970 stage play I’ve Seen You Cut Lemons by Ted Allan, Love Streams is Cassavetes’ final masterpiece, sadly unavailable on any home video format. Both a stunning summation and exquisite farewell to everything that had come before in terms of his thematic concerns, it’s a final prayer for love and empathy, communication and understanding that centres on a brother and sister struggling to keep their grip on the very edges of their worlds.

Although he would go on to direct one more feature subsequently, Cassavetes was little more than a hired hand on the dreadful Big Trouble the following year, so the final shot of Love Streams presents an image of heartbreaking, seemingly prescient finality. Both Cassavetes and Rowlands give remarkable performances, hers sounding echoes of both A Woman under the Influence’s Mabel Longhetti and Opening Night’s Myrtle Gordon, his a hollow shell of Husbands’ Gus Demetri.

It’s a film that sees Cassavetes take an achingly poetic leap into new territory in its final third, his closing tempest making a mockery of Mazursky’s. The formal qualities of Love Streams show the filmmaker scaling new heights, and for my money it’s the pinnacle of his achievements as a filmmaker.