The history of cinema is littered with complex, troubling characters that reflect, accentuate or illuminate the darker recesses of society and the individual human psyche. Forty years ago, Martin Scorsese’s Taxi Driver unleashed one of cinema’s most disturbing but iconic creations in the shape of Travis Bickle, brought to life on screen with committed intensity by Robert De Niro.

This honourably discharged US Marine turned vigilante killer is the diseased heart of a searing and damning portrait of American urban life in the materialistic post-Watergate, post-Vietnam world. An alienated anti-hero for the age, Travis both fed off and fed into the perceived moral degeneration observed from the isolated vantage point of the yellow cab he steers around the then garbage-strewn, mean streets of New York.

A brooding, waking-dream of a film, Taxi Driver eventually explodes into violence as Travis’s pent-up psychotic rage forces its way out of his mind and into reality. Travis’s symbolic, blood-drenched cleansing of the soul was so much of a concern to the MPAA that Scorsese desaturated the colours during the film’s deeply unsettling, censor-baiting climax. Its power to shock was not diminished by this slight artistic compromise. An exemplary melding of imagery, dialogue, music, artistic vision and technical mastery, Taxi Driver deservedly won that year’s Palme d’Or and was also nominated for four Academy Awards.

Scorsese’s production featured a roll call of talent that, on reflection, virtually assured that it would go on to be deemed an American classic. Written by Paul Schrader, scored by the great Bernard Herrmann, who would sadly die before the film’s release, and featuring makeup work by Dick Smith, the peerless off-screen crew were joined on it by Cybill Shepherd, Harvey Keitel, Peter Boyle and then 13-year-old Jodie Foster in support of De Niro’s central performance.

Schrader wrote the script in a month while going through his own personal problems and took inspiration from Dostoevsky’s Notes from Underground and from the diaries of Arthur Bremer, who shot presidential candidate George Wallace in 1972. The threads of real life would be mirrored and chillingly reconnected to Taxi Driver in 1981 when John Hinckley Jr would attempt to assassinate President Reagan in a twisted effort to impress Jodie Foster, with whom Hinckley Jr had developed a dangerous obsession.

Scorsese assimilated the sensibilities and traits of classical and New Hollywood filmmaking, European arthouse cinema, film noir and, climactically, exploitation movies in realising Schrader’s script. As for Herrmann’s swansong score, the melancholy jazz and plaintive saxophone fittingly speak of loneliness and isolation, while the rumblings of the harp, brass and drum movements audibly point to the growing pressure on Travis and the oncoming eruption of his psychosis.

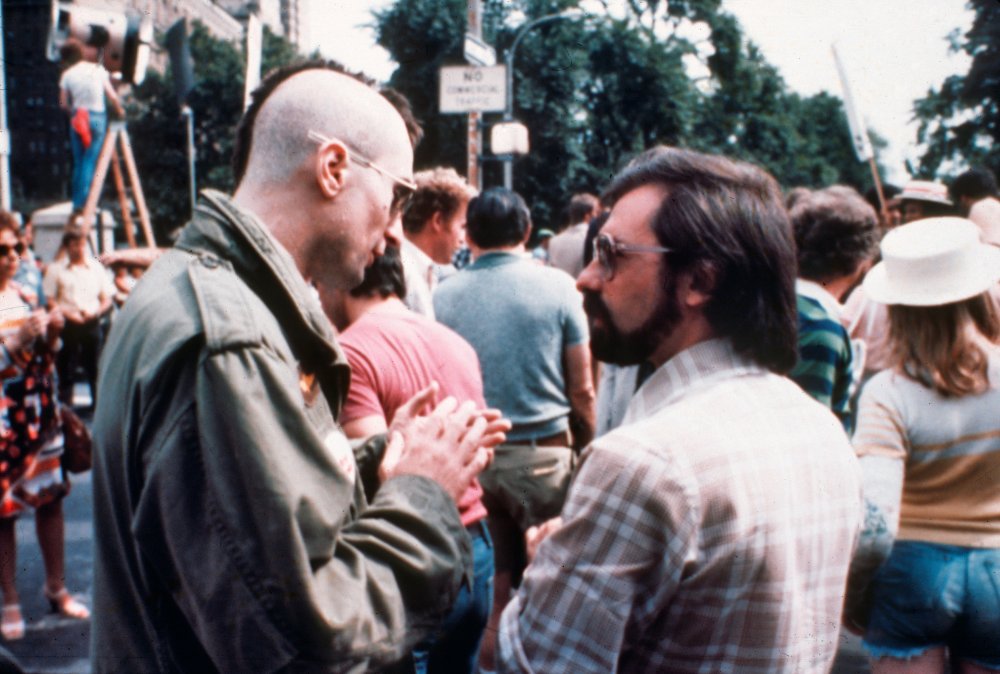

Robert De Niro and Martin Scorsese during production of Taxi Driver (1976)

Confrontational, reflective and (as unfortunately transpired) grimly prophetic, Taxi Driver’s vision of social corrosion, moral corruption and personal trauma remains as much of a gut-punch now as it was on release. As for the film’s that influenced Scorsese’s early masterpiece narratively and stylistically, here are five of the most prominent.

The Searchers (1956)

Director John Ford

Taxi Driver pays clear homage to John Ford’s The Searchers, which was named the greatest American western in the American Film Institute’s 2008 poll. The central figure of Frank S. Nugent’s screenplay is Ethan Edwards, portrayed by Ford regular John Wayne. In something of a departure for an actor who came to embody American ideals of heroism on screen and off, Wayne’s Ethan Edwards is no hero and displays less than admirable qualities. Both war veterans, Ethan and Travis seek redemption through ‘rescuing’ females who may not want/need saving. Loners with a propensity for violence, their self-imposed moral missions drive the respective narratives.

The Wrong Man (1956)

Director Alfred Hitchcock

On a surface level, the story of Manny Balestrero (Henry Fonda), a working musician and happily married father of two wrongly accused of armed robbery, has little in common with that of Travis Bickle’s own personal torments. Elements of Alfred Hitchcock’s docudrama The Wrong Man were, however, brought to bear on the shooting style of Taxi Driver. In a 1998 interview with Roger Ebert, Scorsese stated that the film “has more to do with the camera movements in Taxi Driver than any other picture I can think of. It’s such a heavy influence because of the sense of guilt and paranoia.”

Pickpocket (1959)

Director Robert Bresson

Robert Bresson’s self-penned character study of petty thief Michel (Martin LaSalle) is, like the titular figure in the acclaimed director’s Diary of a Country Priest (1951), a clear influence on Scorsese and Schrader’s tortured protagonist. Michel’s confessional voiceover narration, diary writing and voyeuristic tendencies are exhibited in both Taxi Driver’s narrative style and Travis’s character traits. Transcendental, existential and non-judgemental, Pickpocket and Taxi Driver explore the immoral reasoning that drives Michel and Travis to take the course of actions driven by the personal problems and social situations the respective lead characters find themselves in.

2 or 3 Things I Know about Her (1967)

Director Jean-Luc Godard

As passionate and knowledgeable a cinephile as he is talented as a filmmaker, it’s not surprising that Scorsese openly acknowledges the debt he owes to the French new wave and the films of Jean-Luc Godard in particular. In one scene from the French director’s 2 or 3 Things I Know about Her, the camera closes in and lingers on the surface of a cup of coffee, a shot recreated in Taxi Driver as Travis drops an Alka-Seltzer into a glass of water before staring intently at the fizzing mixture. It’s a small but important tip of the hat in a film that wears a myriad of influences proudly on its sleeve.

The Merchant of Four Seasons (1971)

Director Rainer Werner Fassbinder

In recent years, Scorsese has talked of the influence that the late Rainer Werner Fassbinder’s work had on Taxi Driver and the director’s filmmaking in general. Singling out The Merchant of Four Seasons, one of the New German Cinema auteurist’s most celebrated melodramas, Scorsese said “it had a kind of brutal honesty about the way the camera looked at the characters – at the actors”. A bleak tale of depression, self-destruction and familial discord, The Merchant of Four Seasons is not short of stark imagery and unvarnished realism. Amid the visual symbolism and colour coding of Taxi Driver, these stylistic elements also make their presence felt.