Michel Ciment: You have given almost no interviews on Barry Lyndon. Does this decision relate to this film particularly, or is it because you are reluctant to speak about your work?

Stanley Kubrick: I suppose my excuse is that the picture was ready only a few weeks before it opened and I really had no time to do any interviews. But if I’m to be completely honest, it’s probably due more to the fact that I don’t like doing interviews. There is always the problem of being misquoted or, what’s even worse, of being quoted exactly, and having to see what you’ve said in print. Then there are the mandatory — “How did you get along with actor X, Y or Z?” — “Who really thought of good idea A, B or C?” I think Nabokov may have had the right approach to interviews. He would only agree to write down the answers and then send them on to the interviewer who would then write the questions.

Do you feel that Barry Lyndon is a more secret film, more difficult to talk about?

Not really. I’ve always found it difficult to talk about any of my films. What I generally manage to do is to discuss the background information connected with the story, or perhaps some of the interesting facts which might be associated with it. This approach often allows me to avoid the “What does it mean? Why did you do it?” questions. For example, with Dr. Strangelove I could talk about the spectrum of bizarre ideas connected with the possibilities of accidental or unintentional warfare.2001: A Space Odyssey allowed speculation about ultra-intelligent computers, life in the universe, and a whole range of science-fiction ideas. A Clockwork Orangeinvolved law and order, criminal violence, authority versus freedom, etc. With Barry Lyndon you haven’t got these topical issues to talk around, so I suppose that does make it a bit more difficult.

Your last three films were set in the future. What led you to make an historical film?

I can’t honestly say what led me to make any of my films. The best I can do is to say I just fell in love with the stories. Going beyond that is a bit like trying to explain why you fell in love with your wife: she’s intelligent, has brown eyes, a good figure. Have you really said anything? Since I am currently going through the process of trying to decide what film to make next, I realize just how uncontrollable is the business of finding a story, and how much it depends on chance and spontaneous reaction. You can say a lot of “architectural” things about what a film story should have: a strong plot, interesting characters, possibilities for cinematic development, good opportunities for the actors to display emotion, and the presentation of its thematic ideas truthfully and intelligently. But, of course, that still doesn’t really explain why you finally chose something, nor does it lead you to a story. You can only say that you probably wouldn’t choose a story that doesn’t have most of those qualities.

Since you are completely free in your choice of story material, how did you come to pick up a book by Thackeray, almost forgotten and hardly republished since the nineteenth century?

I have had a complete set of Thackeray sitting on my bookshelf at home for years, and I had to read several of his novels before reading Barry Lyndon. At one time,Vanity Fair interested me as a possible film but, in the end, I decided the story could not be successfully compressed into the relatively short time-span of a feature film. This problem of length, by the way, is now wonderfully accommodated for by the television miniseries which, with its ten- to twelve-hour length, pressed on consecutive nights, has created a completely different dramatic form. Anyway, as soon as I read Barry Lyndon I became very excited about it. I loved the story and the characters, and it seemed possible to make the transition from novel to film without destroying it in the process. It also offered the opportunity to do one of the things that movies can do better than any other art form, and that is to present historical subject matter. Description is not one of the things that novels do best but it is something that movies do effortlessly, at least with respect to the effort required of the audience. This is equally true for science-fiction and fantasy, which offer visual challenges and possibilities you don’t find in contemporary stories.

How did you come to adopt a third-person commentary instead of the first-person narrative which is found in the book?

I believe Thackeray used Redmond Barry to tell his own story in a deliberately distorted way because it made it more interesting. Instead of the omniscient author, Thackeray used the imperfect observer, or perhaps it would be more accurate to say the dishonest observer, thus allowing the reader to judge for himself, with little difficulty, the probable truth in Redmond Barry’s view of his life. This technique worked extremely well in the novel but, of course, in a film you have objective reality in front of you all of the time, so the effect of Thackeray’s first-person story-teller could not be repeated on the screen. It might have worked as comedy by the juxtaposition of Barry’s version of the truth with the reality on the screen, but I don’t think that Barry Lyndon should have been done as a comedy.

You didn’t think of having no commentary?

There is too much story to tell. A voice-over spares you the cumbersome business of telling the necessary facts of the story through expositional dialogue scenes which can become very tiresome and frequently unconvincing: “Curse the blasted storm that’s wrecked our blessed ship!” Voice-over, on the other hand, is a perfectly legitimate and economical way of conveying story information which does not need dramatic weight and which would otherwise be too bulky to dramatize.

But you use it in other way — to cool down the emotion of a scene, and to anticipate the story. For instance, just after the meeting with the German peasant girl — a very moving scene — the voice-over compares her to a town having been often conquered by siege.

In the scene that you’re referring to, the voice-over works as an ironic counterpoint to what you see portrayed by the actors on the screen. This is only a minor sequence in the story and has to be presented with economy. Barry is tender and romantic with the girl but all he really wants is to get her into bed. The girl is lonely and Barry is attractive and attentive. If you think about it, it isn’t likely that he is the only soldier she has brought home while her husband has been away to the wars. You could have had Barry give signals to the audience, through his performance, indicating that he is really insincere and opportunistic, but this would be unreal. When we try to deceive we are as convincing as we can be, aren’t we?

The film’s commentary also serves another purpose, but this time in much the same manner it did in the novel. The story has many twists and turns, and Thackeray uses Barry to give you hints in advance of most of the important plot developments, thus lessening the risk of their seeming contrived.

When he is going to meet the Chevalier Balibari, the commentary anticipates the emotions we are about to see, thus possibly lessening their effect.

Barry Lyndon is a story which does not depend upon surprise. What is important is not what is going to happen, but how it will happen. I think Thackeray trades off the advantage of surprise to gain a greater sense of inevitability and a better integration of what might otherwise seem melodramatic or contrived. In the scene you refer to where Barry meets the Chevalier, the film’s voice-over establishes the necessary groundwork for the important new relationship which is rapidly to develop between the two men. By talking about Barry’s loneliness being so far from home, his sense of isolation as an exile, and his joy at meeting a fellow countryman in a foreign land, the commentary prepares the way for the scenes which are quickly to follow showing his close attachment to the Chevalier. Another place in the story where I think this technique works particularly well is where we are told that Barry’s young son, Bryan, is going to die at the same time we watch the two of them playing happily together. In this case, I think the commentary creates the same dramatic effect as, for example, the knowledge that the Titanic is doomed while you watch the carefree scenes of preparation and departure. These early scenes would be inexplicably dull if you didn’t know about the ship’s appointment with the iceberg. Being told in advance of the impending disaster gives away surprise but creates suspense.

There is very little introspection in the film. Barry is open about his feelings at the beginning of the film, but then he becomes less so.

At the beginning of the story, Barry has more people around him to whom he can express his feelings. As the story progresses, and particularly after his marriage, he becomes more and more isolated. There is finally no one who loves him, or with whom he can talk freely, with the possible exception of his young son, who is too uoung to be of much help. At the same time I don’t think that the lack of introspective dialogue scenes are any loss to the story. Barry’s feelings are there to be seen as he reacts to the increasingly difficult circumstances of his life. I think this is equally true for the other characters in the story. In any event, scenes of people talking about themselves are often very dull.

In contrast to films which are preoccupied with analyzing the psychology of the characters, yours tend to maintain a mystery around them. Reverend Runt, for instance, is a very opaque person. You don’t know exactly what his motivations are.

But you know a lot about Reverend Runt, certainly all that is necessary. He dislikes Barry. He is secretly in love with Lady Lyndon, in his own prim, repressed, little way. His little smile of triumph, in the scene in the coach, near the end of the film, tells you all you need to know regarding the way he feels about Barry’s misfortune, and the way things have worked out. You certainly don’t have the time in a film to develop the motivations of minor characters.

Lady Lyndon is even more opaque.

Thackeray doesn’t tell you a great deal about her in the novel. I found that very strange. He doesn’t give you a lot to go on. There are, in fact, very few dialogue scenes with her in the book. Perhaps he meant her to be something of a mystery. But the film gives you a sufficient understanding of her anyway.

You made important changes in your adaptation, such as the invention of the last duel, and the ending itself.

Yes, I did, but I was satisfied that they were consistent with the spirit of the novel and brought the story to about the same place the novel did, but in less time. In the book, Barry is pensioned off by Lady Lyndon. Lord Bullingdon, having been believed dead, returns from America. He finds Barry and gives him a beating. Barry, tended by his mother, subsequently dies in prison, a drunk. This, and everything that went along with it in the novel to make it credible would have taken too much time on the screen. In the film, Bullingdon gets his revenge and Barry is totally defeated, destined, one can assume, for a fate not unlike that which awaited him in the novel.

And the scene of the two homosexuals in the lake was not in the book either.

The problem here was how to get Barry out of the British Army. The section of the book dealing with this is also fairly lengthy and complicated.

The function of the scene between the two gay officers was to provide a simpler way for Barry to escape. Again, it leads to the same end result as the novel but by a different route. Barry steals the papers and uniform of a British officer which allow him to make his way to freedom. Since the scene is purely expositional, the comic situation helps to mask your intentions.

Were you aware of the multiple echoes that are found in the film: flogging in the army, flogging at home, the duels, etc., and the narrative structure resembling that ofA Clockwork Orange? Does this geometrical pattern attract you?

The narrative symmetry arose primarily out of the needs of telling the story rather than as part of a conscious design. The artistic process you go through in making a film is as much a matter of discovery as it is the execution of a plan. Your first responsibility in writing a screenplay is to pay the closest possible attention to the author’s ideas and make sure you really understand what he has written and why he has written it. I know this sounds pretty obvious but you’d be surprised how often this is not done. There is a tendency for the screenplay writer to be “creative” too quickly. The next thing is to make sure that the story survives the selection and compression which has to occur in order to tell it in a maximum of three hours, and preferably two. This phase usually seals the fate of most major novels, which really need the large canvas upon which they are presented.

In the first part of A Clockwork Orange, we were against Alex. In the second part, we were on his side. In this film, the attraction/repulsion feeling towards Barry is present throughout.

Thackeray referred to it as “a novel without a hero”. Barry is naive and uneducated. He is driven by a relentless ambition for wealth and social position. This proves to be an unfortunate combination of qualities which eventually lead to great misfortune and unhappiness for himself and those around him. Your feelings about Barry are mixed but he has charm and courage, and it is impossible not to like him despite his vanity, his insensitivity and his weaknesses. He is a very real character who is neither a conventional hero nor a conventional villain.

The feeling that we have at the end is one of utter waste.

Perhaps more a sense of tragedy, and because of this the story can assimilate the twists and turns of the plot without becoming melodrama. Melodrama uses all the problems of the world, and the difficulties and disasters which befall the characters, to demonstrate that the world is, after all, a benevolent and just place.

The last sentence which says that all the characters are now equal can be taken as a nihilistic or religious statement. From your films, one has the feeling that you are a nihilist who would like to believe.

I think you’ll find that it is merely an ironic postscript taken from the novel. Its meaning seems quite clear to me and, as far as I’m concerned, it has nothing to do with nihilism or religion.

One has the feeling in your films that the world is in a constant state of war. The apes are fighting in 2001. There is fighting, too, in Paths Of Glory, and Dr. Strangelove. In Barry Lyndon, you have a war in the first part, and then in the second part we find the home is a battleground, too.

Drama is conflict, and violent conflict does not find its exclusive domain in my films. Nor is it uncommon for a film to be built around a situation where violent conflict is the driving force. With respect to Barry Lyndon, after his successful struggle to achieve wealth and social position, Barry proves to be badly unsuited to this role. He has clawed his way into a gilded cage, and once inside his life goes really bad. The violent conflicts which subsequently arise come inevitably as a result of the characters and their relationships. Barry’s early conflicts carry him forth into life and they bring him adventure and happiness, but those in later life lead only to pain and eventually to tragedy.

In many ways, the film reminds us of silent movies. I am thinking particularly of the seduction of Lady Lyndon by Barry at the gambling table.

That’s good. I think that silent films got a lot more things right than talkies. Barry and Lady Lyndon sit at the gaming table and exchange lingering looks. They do not say a word. Lady Lyndon goes out on the balcony for some air. Barry follows her outside. They gaze longingly into each other’s eyes and kiss. Still not a word is spoken. It’s very romantic, but at the same time, I think it suggests the empty attraction they have for each other that is to disappear as quickly as it arose. It sets the stage for everything that is to follow in their relationship. The actors, the images and the Schubert worked well together, I think.

Did you have Schubert’s Trio in mind while preparing and shooting this particular scene?

No, I decided on it while we were editing. Initially, I thought it was right to use only eighteenth-century music. But sometimes you can make ground-rules for yourself which prove unnecessary and counter-productive. I think I must have listened to every LP you can buy of eighteenth-century music. One of the problems which soon became apparent is that there are no tragic love-themes in eighteenth-century music. So eventually I decided to use Schubert’s Trio in E Flat, Opus 100, written in 1828. It’s a magnificent piece of music and it has just the right restrained balance between the tragic and the romantic without getting into the headier stuff of later Romanticism.

You also cheated in another way by having Leonard Rosenman orchestrate Handel’s Sarabande in a more dramatic style than you would find in eighteenth-century composition.

This arose from another problem about eighteenth-century music — it isn’t very dramatic, either. I first came across the Handel theme played on a guitar and, strangely enough, it made me think of Ennio Morricone. I think it worked very well in the film, and the very simple orchestration kept it from sounding out of place.

It also accompanies the last duel — not present in the novel — which is one of the most striking scenes in the film and is set in a dovecote.

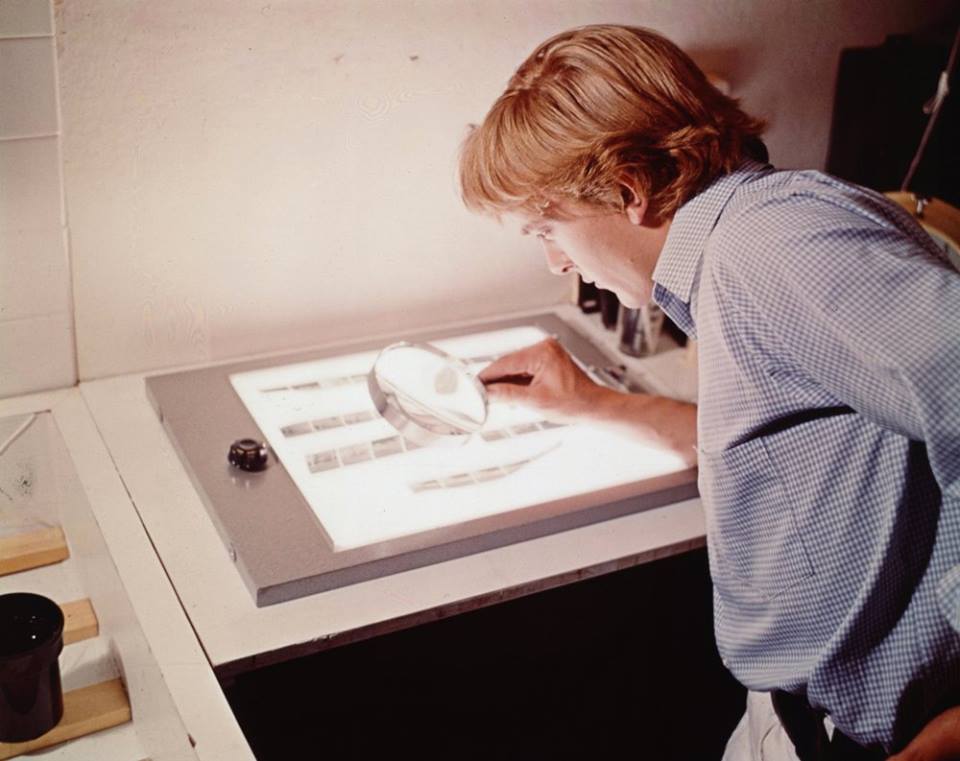

The setting was a tithe barn which also happened to have a lot of pigeons resting in the rafters. We’ve seen many duels before in films, and I wanted to find a different and interesting way to present the scene. The sound of the pigeons added something to this, and, if it were a comedy, we could have had further evidence of the pigeons. Anyway, you tend to expect movie duels to be fought outdoors, possibly in a misty grove of trees at dawn. I thought the idea of placing the duel in a barn gave it an interesting difference. This idea came quite by accident when one of the location scouts returned with some photographs of the barn. I think it was Joyce who observed that accidents are the portals to discovery. Well, that’s certainly true in making films. And perhaps in much the same way, there is an aspect of film-making which can be compared to a sporting contest. You can start with a game plan but depending on where the ball bounces and where the other side happens to be, opportunities and problems arise which can only be effectively dealt with at that very moment.

In 2001: A Space Odyssey, for example, there seemed no clever way for HAL to learn that the two astronauts distrusted him and were planning to disconnect his brain. It would have been irritatingly careless of them to talk aloud, knowing that HAL would hear and understand them. Then the perfect solution presented itself from the actual phsical layout of the space pod in the pod bay. The two men went into the pod and turned off every switch to make them safe from HAL’s microphones. They sat in the pod facing each other and in the center of the shot, visible through the sound-proof glass port, you could plainly see the red glow of HAL’s bug-eye lens, some fifteen feet away. What the conspirators didn’t think of was that HAL would be able to read their lips.

Did you find it more constricting, less free, making an historical film where we all have precise conceptions of a period? Was it more of a challenge?

No, because at least you know what everything looked like. In 2001: A Space Odyssey everything had to be designed. But neither type of film is easy to do. In historical and futuristic films, there is an inverse relationship between the ease the audience has taking in at a glance the sets, costumes and decor, and the film-maker’s problems in creating it. When everything you see has to be designed and constructed, you greatly increase the cost of the film, add tremendously to all the normal problems of film-making, making it virtually impossible to have the flexibility of last-minute changes which you can manage in a contemporary film.

You are well-known for the thoroughness with which you accumulate information and do research when you work on a project. Is it for you the thrill of being a reporter or a detective?

I suppose you could say it is a bit like being a detective. On Barry Lyndon, I accumulated a very large picture file of drawings and paintings taken from art books. These pictures served as the reference for everything we needed to make — clothes, furniture, hand props, architecture, vehicles, etc. Unfortunately, the pictures would have been too awkward to use while they were still in the books, and I’m afraid we finally had very guiltily to tear up a lot of beautiful art books. They were all, fortunately, still in print which made it seem a little less sinful. Good research is an absolute necessity and I enjoy doing it. You have an important reason to study a subject in much greater depth than you would ever have done otherwise, and then you have the satisfaction of putting the knowledge to immediate good use. The designs for the clothes were all copied from drawings and paintings of the period. None of them were designed in the normal sense. This is the best way, in my opinion, to make historical costumes. It doesn’t seem sensible to have a designer interpret — say — the eighteenth century, using the same picture sources from which you could faithfully copy the clothes. Neither is there much point sketching the costumes again when they are already beautifully represented in the paintings and drawings of the period. What is very important is to get some actual clothes of the period to learn how they were originally made. To get them to look right, you really have to make them the same way. Consider also the problem of taste in designing clothes, even for today. Only a handful of designers seem to have a sense of what is striking and beautiful. How can a designer, however brilliant, have a feeling for the clothes of another period which is equal to that of the people and the designers of the period itself, as recorded in their pictures? I spent a year preparing Barry Lyndon before the shooting began and I think this time was very well spent. The starting point and sine qua non of any historical or futuristic story is to make you believe what you see.

The danger in an historical film is that you lose yourself in details, and become decorative.

The danger connected with any multi-faceted problem is that you might pay too much attention to some of the problems to the detriment of others, but I am very conscious of this and I make sure I don’t do that.

Why do you prefer natural lighting?

Because it’s the way we see things. I have always tried to light my films to simulate natural light; in the daytime using the windows actually to light the set, and in night scenes the practical lights you see in the set. This approach has its problems when you can use bright electric light sources, but when candelabras and oil lamps are the brightest light sources which can be in the set, the difficulties are vastly increased. Prior to Barry Lyndon, the problem has never been properly solved. Even if the director and cameraman had the desire to light with practical light sources, the film and the lenses were not fast enough to get an exposure. A 35mm movie camera shutter exposes at about 1/50 of a second, and a useable exposure was only possible with a lens at least 100% faster than any which had ever been used on a movie camera. Fortunately, I found just such a lens, one of a group of ten which Zeiss had specially manufactured for NASA satellite photography. The lens had a speed of fO.7, and it was 100% faster than the fastest movie lens. A lot of work still had to be done to it and to the camera to make it useable. For one thing, the rear element of the lens had to be 2.5mm away from the film plane, requiring special modification to the rotating camera shutter. But with this lens it was now possible to shoot in light conditions so dim that it was difficult to read. For the day interior scenes, we used either the real daylight from the windows, or simulated daylight by banking lights outside the windows and diffusing them with tracing paper taped on the glass. In addition to the very beautiful lighting you can achieve this way, it is also a very practical way to work. You don’t have to worry about shooting into your lighting equipment. All your lighting is outside the window behind tracing paper, and if you shoot towwards the window you get a very beautiful and realistic flare effect.

How did you decide on Ryan O’Neal?

He was the best actor for the part. He looked right and I was confident that he possessed much greater acting ability than he had been allowed to show in many of the films he had previously done. In retrospect, I think my confidence in him was fully justified by his performance, and I still can’t think of anyone who would have been better for the part. The personal qualities of an actor, as they relate to the role, are almost as important as his ability, and other actors, say, like Al Pacino, Jack Nicholson or Dustin Hoffman, just to name a few who are great actors, would nevertheless have been wrong to play Barry Lyndon. I liked Ryan and we got along very well together. In this regard the only difficulties I have ever had with actors happened when their acting technique wasn’t good enough to do something you asked of them. One way an actor deals with this difficulty is to invent a lot of excuses that have nothing to do with the real problem. This was very well represented in Truuffaut’s Day For Night when Valentina Cortese, the star of the film within the film, hadn’t bothered to learn her lines and claimed her dialogue fluffs were due to the confusion created by the script girl playing a bit part in the scene.

How do you explain some of the misunderstandings about the film by the American press and the English press?

The American press was predominantly enthusiastic about the film, and Time magazine ran a cover story about it. The international press was even more enthusiastic. It is true that the English press was badly split. But from the very beginning, all of my films have divided the critics. Some have thought them wonderful, and others have found very little good to say. But subsequent critical opinion has always resulted in a very remarkable shift to the favorable. In one instance, the same critic who originally rapped the film has several years later put it on an all-time best list. But, of course, the lasting and ultimately most important reputation of a film is not based on reviews, but on what, if anything, people say about it over the years, and on how much affection for it they have.

You are an innovator, but at the same time you are very conscious of tradition.

I try to be, anyway. I think that one of the problems with twentieth-century art is its preoccupation with subjectivity and originality at the expense of everything else. This has been especially true in painting and music. Though initially stimulating, this soon impeded the full development of any particular style, and rewarded uninteresting and sterile originality. At the same time, it is very sad to say, films have had the opposite problem — they have consistently tried to formalize and repeat success, and they have clung to a form and style introduced in their infancy. The sure thing is what everone wants, and originality is not a nice word in this context. This is true despite the repeated example that nothing is as dangerous as a sure thing.

You have abandoned original film music in your last three films.

Exclude a pop music score from what I am about to say. However good our best film composers may be, they are not a Beethoven, a Mozart or a Brahms. Why use music which is less good when there is such a multitude of great orchestral music available from the past and from our own time? When you’re editing a film, it’s very helpful to be able to try out different pieces of music to see how they work with the scene. This is not at all an uncommon practice. Well, with a little more care and thought, these temporary music tracks can become the final score. When I had completed the editing of 2001: A Space Odyssey, I had laid in temporary music tracks for almost all of the music which was eventually used in the film. Then, in the normal way, I engaged the services of a distinguished film composer to write the score. Although he and I went over the picture very carefully, and he listened to these temporary tracks (Strauss, Ligeti, Khatchaturian) and agreed that they worked fine and would serve as a guide to the musical objectives of each sequence he, nevertheless, wrote and recorded a score which could not have been more alien to the music we had listened to, and much more serious than that, a score which, in my opinion, was completely inadequate for the film. With the premiere looming up, I had no time left even to think about another score being written, and had I not been able to use the music I had already selected for the temporary tracks I don’t know what I would have done. The composer’s agent phoned Robert O’Brien, the then head of MGM, to warn him that if I didn’t use his client’s score the film would not make its premiere date. But in that instance, as in all others, O’Brien trusted my judgment. He is a wonderful man, and one of the very few film bosses able to inspire genuine loyalty and affection from his film-makers.

Why did you choose to have only one flashback in the film: the child falling from the horse?

I didn’t want to spend the time which would have been required to show the entire story action of young Bryan sneaking away from the house, taking the horse, falling, being found, etc. Nor did I want to learn about the accident solely through the dialogue scene in which the farm workers, carrying the injured boy, tell Barry. Putting the flashback fragment in the middle of the dialogue scene seemed to be the right thing to do.

Are your camera movements planned before?

Very rarely. I think there is virtually no point putting camera instructions into a screenplay, and only if some really important camera idea occurs to me, do I write it down. When you rehearse a scene, it is usually best not to think about the camera at all. If you do, I have found that it invariably interferes with the fullest exploration of the ideas of the scene. When, at last, something happens which you know is worth filming, that is the time to decide how to shoot it. It is almost but not quite true to say that when something really exciting and worthwhile is happening, it doesn’t matter how you shoot it. In any event, it never takes me long to decide on set-ups, lighting or camera movements. The visual part of film making has always come easiest to me, and that is why I am careful to subordinate it to the story and the performances.

Do you like writing alone or would you like to work with a script writer?

I enjoy working with someone I find stimulating. One of the most fruitful and enjoyable collaborations I have had was with Arthur C. Clarke in writing the story of2001: A Space Odyssey. One of the paradoxes of movie writing is that, with a few notable exceptions, writers who can really write are not interested in working on film scripts. They quite correctly regard their important work as being done for publication. I wrote the screenplay for Barry Lyndon alone. The first draft took three or four months but, as with all my films, the subsequent writing process never really stopped. What you have written and is yet unfilmed is inevitably affected by what has been filmed. New problems of content or dramatic weight reveal themselves. Rehearsing a scene can also cause script changes. However carefully you think about a scene, and however clearly you believe you have visualized it, it’s never the same when you finally see it played. Sometimes a totally new idea comes up out of the blue, during a rehearsal, or even during actual shooting, which is simply too good to ignore. This can necessitate the new scene being worked out with the actors right then and there. As long as the actors know the objectives of the scene, and understand their characters, this is less difficult and much quicker to do than you might imagine.

“My God!” Hitchcock exclaimed to screenwriter Howard Fast. “I’ve just seen Michelangelo Antonioni’s Blowup. These Italian directors are a century ahead of me in terms of technique. What have I been doing all this time?”

Shocked into the new, Hitchcock repeatedly watched Blowup. Test footage for Kaleidoscope – the project that would become Frenzy – is suffused with similar dreamy colours and jaded infatuation with swinging London.

Dok se autobus približavao Toledu, osećao sam kao da se približava nekakvoj opasnosti. I zaista, kad se ukazao grad, luka i sumanuta kamena izbočina u meandru reke Taho, mislio sam da će srce da mi stane. Kakve su to priče da El Greko nije mogao da dođe do posla u Eskorijalu, da nije bio prihvaćen od španskog dvora i da se zbog toga skrasio u Toledu. Činjenično stanje je sledeće: Toledo je bio jedini grad gde je ovaj čovek fizički mogao da opstane, grad po njegovoj meri, jedini grad u kojem je njegovo delo moglo neometano da poraste. Poslovi umetnosti su u Božijim rukama. Kad On odluči da nastane slikarstvo Dominikosa Teotokupulosa, onda su slikarevi roditelji mogli da prave slikara gde hoće – i na Kritu, zašto da ne – slikar je u Toledo morada da stigne. Sklon sam da verujem da je Toledo sagrađen isključivo zato da bi se u njemu jednoga dana nastanio ovaj Grk, čiji su roditelji pobegli ispred Turaka na Krit, on sam opet sa Krita u Veneciju, zatim iz prevelike i preblistave venecijanske i ticijanovske slikarske veštine u Madrid, i najzad u ovaj grad, u kojem su, kad je Teotokopulos stigao, žestoko živeli Jevreji (bogati i osioni), hrišćani najbliži nebu (episkopi i vojskovođe istovremeno), Grci izbeglice (vešti poslovni ljudi), i još ko zna kakav svet putnika i izdajnika, prosjaka i filozofa, kaluđera dominikanaca i grofova (od Orgaza)…

U kapeli svetog Tome. Prvi susret sa slikom Sahrana grofa od Orgaza. Nikada i nigde i ni u jednoj zemlji i ni u jednoj prilici i ni na jednom platnu i na na jednom zidu nije napravljeno ništa slično i ništa približno ovoj slici. Delo je jednostavno i opet neuhvatljivo, istovremeno otvoreno za svakog i u direktnoj vezi sa Bogom, klasično i moderno, divlje i tiho, sočno i oporo, delikatno i presno, ovlaš naslikano i apsolutno.

Kao da mi se neizmerno bogatstvo slučilo na glavu.

Mića Popović, dnevnik iz Španije

Bolje je biti neprijatelj naroda nego neprijatelj stvarnosti.

Pazolini

“I’ve always lived off my artwork all my life. I’ve lived all over the world. I’ve had fourteen common law wives. I’ve never needed money because I’m talented. Talent is better than money because it’s always with you. Let me give you an example. Back in 1970 I was getting dinner with a Japanese model at the Sao Paulo Hilton in Brazil. This guy from Texas was sitting at the table next to me, and he’s trying to order a steak, but he keeps sending it back to the kitchen. He keeps saying: ‘The steaks are better in Texas.’ After the second time he sends it back, the master chef comes out, and I hear him say in Portuguese: ‘I’m going to kill this man!’ Now being a Galician myself, I know the character of the Latin American people. If a French person says he’s going to kill you, you don’t have to worry. The French are lovers and all lovers are cowards. Trust me—several of my former wives are French. I know this. But when a Latin American tells you that he’s going to kill you, it’s time to leave. So I walked over to the man’s table and bought him a bottle of wine, and I talked with him about Texas. I knew all about Texas because I competed in fishing tournaments there. After a few minutes of talking, I tell the man: ‘If you order one more steak, you’re going to get killed with a machete.’ So he took my advice and he left. The entire restaurant staff came out and started singing to me with tambourines. They brought out free wine and a full spread. They said, ‘Your money is no good here.’ The Japanese model was so impressed. See what I mean? Talent.”

Humans of New York

“Ono što hoću da vam kazem je da Oluje više neće biti, Srbija je dovoljno jaka da brine o svom narodu i nikome više nikada neće dozvoliti takav pogrom”.

Aleksandar Vučić, Zemun, 5. avgust 2106. godine

“Nikada više ustaška vlast neće moći oružanim putem da dođe. Nikada više srpska Krajina neće biti Hrvatska, nego će krajinski Srbi sa svojim sunarodnicima živeti u Velikoj Srbiji.”

Aleksandar Vučić, Glina, 20. marta 1995. godine.

“Ukoliko se njihova zastava bude vijorila na pobedničkom postolju, pored nje neće biti srpske”, rekao je ministar sporta u tehničkoj Vladi Srbije Vanja Udovičić gostujuči sinoć na RTS-u.

Srpski sportisti su, prema rečima Udovičića, dobili instrukcije da ne treba da se susreću i intimiziraju sa sportistima sa Kosova. Dodao je ipak da će sa sa njima takmičiti ako do toga uopšte i dođe.

Što više o ovome razmišljam, to mi izgleda sve logičnije: svi mi, i cela ova zemlja s nama, verovatno uopšte ne postojimo „u stvarnosti“; mi stanujemo samo u snu jednog čoveka, mi smo izmaštani statisti njegove privatne psihodrame. Ako se sanjač probudi, najebali smo: raspršićemo se kao avetinje, jer to i jesmo. U nešto optimističkijoj verziji: stvarni „mi“ pak negde postojimo, ali ne možemo da dopremo do sebe – opet, zato što smo zarobljeni u snu onog već spominjanog; da bismo se uopšte mogli susresti i spojiti sa svojim realnim egzistencijama, prvo bismo morali da se oslobodimo iz tog psihozatočeništva.

Ne, nisam gutao lude gljive niti farmakološke psihoaktivne supstance, nego samo pokušavam da objasnim (najpre samom sebi) „kako je sve ovo moguće“, a da mi to objašnjenje ne zazvuči sasvim idiotski i izuzetno uvredljivo. Plus depresivno. U tom kontekstu, neka vrsta psihodeličnog tumačenja Ovoga Nečega po čemu tumaramo kao po nekakvoj pustinji realnosti deluje mi kao manje strašno od odviše banalne istine da smo naprosto samoizručeni u ruke jednog pretencioznog diletanta krajnje mračne istorije, smušene sadašnjosti i nevesele budućnosti, te njegovih još neverovatnijih posilnih, batlera, majordoma, ađutanata i adlatusa, inače sve od reda braće i sestara, pošto su svi do jednog i jedne iz istog legla: od Zla oca i Još Gore majke.

Da se razumemo, odavno ja podozrevam da s „našim“ učešćem u stvarnosti nešto fundamentalno nije u redu, ali ono što je definitivno prevagnulo na stranu gornjeg „zaumnog“ tumačenja jesu reči Maje Hidžab Gojković, koja je onu stupidnu i sramnu izložotinu (nemam razloga, osim sasvim formalnih, da za To koristim reč „izložba“) u beogradskoj galeriji Progres, a gde „vise“ radovi svih – ne baš ni tako brojnih – koji su zucnuli nešto protiv Aleksandra Vučića i njegove kamarile, nazvala „konceptualnom umetnošću, nešto poput Marine Abramović“.

Da, ona je to rekla – baš to i baš tako. I sasvim javno i pod svojim imenom: nije bila čak ni skrivena hidžabom. E sad, kontam ja, da živimo u „pravoj“ realnosti, ovako bi nešto bilo sasvim neizgovorljivo i upravo nezamislivo da se izgovori, a čak i ako bi se nekom nastranom greškom u sistemu Uopšte Mogućih Događanja našla neka takva mudrica koja bi to izrekla, tog bi joj trenutka nebo u znak protesta ljosnulo na glavu, čime bi osnovni logički poredak sveta ipak bio iznova uspostavljen. Otuda možda ni mentalna oštećenja koja bismo neizbežno pretrpeli direktnom izloženošću zračenju te izjave ne bi bila trajna. Ovako, bogme… Mrka kapa. Konzervativna procena govori da je oko 16 hiljada triliona moždanih vijuga građanki i građana Republike Srbije starih od 7 do 87 godina trajno i neopozivo uništeno neopreznim i nezaštićenim izlaganjem dejstvu tih reči osobe koja u psihodeličnom svetu u kojem smo zatočeni obavlja funkciju predsednice parlamenta. I kako da se onda ne nadam da taj svet ipak nije „prava“ realnost, nego da je ova negde drugde?! Tja, još samo da nađemo izlaz odavde, pa da begamo!

Sasvim ozbiljno, ovo-u-čemu-živimo odavno je transcendiralo „čisto politički“ problem i postalo je parafenomen psihološke naravi, sa ozbiljnim etičkim, zdravstvenim i dakako moralnim implikacijama. U tom je smislu možda i dobro što je famozna Izložotina napravljena, jer je ona nesumnjivo jasan trag o naravi Ovoga U Čemu Smo, jer nakon nje više niko ne može da se pozove na naivnost i neobaveštenost i nastavi spokojno da tvrdi kako živimo u nečemu što ima makar i konture normalnosti.

Zanimljivo je kako je manje-više svima izmicao jedan apsolutno božanstven detalj: tzv. Informativna služba SNS, koja je navodno priredila ovu Izložotinu (oni koji vole da tvrde da su dobro obavešteni tipuju da su pravi autori profiji iz jedne notorne Agencije za prodaju magle, kopanje nozdrvnih ruda, presipanje šupljina u praznine, rasipanje tuđih para i gubljenje vremena) saopštila je da je u narečenom prostoru izložen samo manji deo (2.523 artefakta, ako sam dobro zapamtio) od „necenzurisanih laži“ o Voljenome i njegovoj bratiji, a da je puni broj tih nepodopština, ne držite me za reč, ali recimo 6.742, tako nekako.

E sad, zamislite ljude koji uredno broje i evidentiraju tzv. negativne sadržaje o nekoj stranci, vladi, predsedniku?! Kako se – a bogme i zašto i čemu? – to uopšte može izbrojati u demokratskom i otvorenom društvu? Kako je ostalom moguće imati iole relevantan uvid u sve što se o bilo kome i čemu govori i piše, utoliko pre što su ovde ubrojani i tvitovi i fejsbuci i svakakva čudesa iz sive zone između privatnog i javnog? Zamislite samo da vam iz američke Demokratske stranke, recimo, zgroženo saopšte da su „O predsedniku Obami objavljena 12.493 negativna medijska sadržaja“, uključujući i onaj kad ga je ugledni mislilac Musavi Džo iz Oklahoma Sitija (preko dana točilac goriva na benzinskoj pumpi) na svom zatvorenom fejsbuk profilu nazvao „napornim seronjom“?! Ne, ne možete da zamislite, naprosto zato što i Obama i njegova „informativna služba“ i građani njegove zemlje stanuju u stvarnosti, kakvoj-takvoj, dalekoj od idealne, ali ipak.

A mi za to vreme glavinjamo beskrajnim zavojitim hodnicima Vučićeve glave (prenakrcanim samo i jedino fotošopiranim autoportretima, bajdvej) panično tražeći izlaz, sve manje se nadajući da ćemo ga naći, pa i tome da još uopšte ima sveta negde napolju, onog pravog, onog u kojem nebesa neizbežno padaju na glavu onima koji prekardaše sa drskim budalaštinama i drugim ritualnim uneređivanjima po pameti i časti umereno razumnih i normalnih ljudi. Vremena je sve manje, nade je sve manje, ali opet, vredi kopati, slutim da Stvarnost ipak nije daleko, ponekad začujem poneki njen odjek, zato se ne treba prepuštati malodušnosti, jer baš bi to voleo onaj koji nas prepredeno ubeđuje da Napolju nema ničega. Naprotiv, Napolju je sve, a Unutra, pravo da vam kažem, nema ničega. Zato toliko i zveči.

Teofil Pančić, Bekstvo iz Vučića

Njih odavno niko ništa ne pita, mogu da ‘nahrane svinje i ne diraju gumbe’ kao Suljo iz vica u eksperimentalnom svemirskom brodu, tj. mogu da kakuckaju po svom i tuđem dvorištu, što obilato koriste, ali ne i da pucaju, čak ni u vazduh. Veća je verovatnoća da će Redžep Tajip Erdogan postati lezbejka kalvinističke veroispovesti koja posvećeno sluša trash metal i onda se kao takva udati za Vladimira V. Putina evoluiralog u brinetu veganku koja svira ritam gitaru u Pussy Riot, nego da se centralni južnoslovenski prostor ponovo nađe u stanju rata koji ne bi bio posve hladan. Nikakve stvarne frke neće biti jer ona sistemski nije moguća, ne postoje nikakve realne i utemeljene pretpostavke za nju, čak ni psihološke, koliko god da se na tome iznova radi. Bombe koje se puštaju u etar, dakle, nisu razorne i ne ubijaju, svakako ne na način devedesetih – one su, međutim, ekološki opasne, jer zagađuju i zasmrđuju. Gadno je živeti uz njih, ali po život je mnogo opasnije prelaziti Kolarčevu ulicu oko podneva. To da ovako smrde uopšte nije čudno s obzirom na njihov hemijski sastav – a bogme i na profil onih koji ih razmenjuju, odatle ne biva vanile i lavande, samo bazdećih supstanci. O čemu je, jebiga, valjalo misliti onda kada smo te puštače nadripolitičkih bombi-smrdulja pokupili s otpada devedesetih i stavili ih u reciklažu, ali sada više vajde od toga nema. Samoosuđeni smo na njih za još nedefinisano dugo vreme, u Srbiji svakako, u Bosni takođe, za Hrvatsku će se ubrzo videti.

Nemogućnost fizičkog ovaploćenja stvarnog sranja koje bi podsećalo na kanibalske događaje iz devedesetih ipak ne znači da se ovim trovačkim mahnitanjem ne treba podrobnije pozabaviti. Mentalna tortura kroz koju prolazimo manje-više svakog leta, a ovog je baš žestoko zaošijana, pokazuje stvarno stanje ne u tzv. regionalnim odnosima, ili srpsko-hrvatskim, ili srpsko-bošnjačkim ili ne znam kojim, nego baš ono što se nastoji prikriti – pravo stanje unutar svake od tih država, patološku sliku stanja tih društava, kidnapovanih i serijski silovanih od dokazano najgorih ljudi koje uopšte ima. A nije problem u tome što ti dokazano najgori uopšte postoje, jer takvog šljama ima svuda, nego što su oni ujedno i dokazano najmoćniji ljudi u tim zemljama; u njih je i moć, i sila, i novac, i institucije (tj. njihove prazne ljušture) i lavovski deo javnog diskursa i štošta još. Zato se ojašenim podanicima i nudi sve radioaktivnije prekoplotiranje i pljuvanje u komšijski tanjir te psovačko nadvikivanje preko ograde; ne bi li podaništvo zaboravilo na mizeriju sopstvenih života, mizeriju koja, uzgred, nišošto nije samo materijalna. I nemojte za sve to kriviti njih, krem našeg ološa, ponovo uzveran u društvene vrhove; ne bi oni bili tu gde jesu da ih većina u svakom od ovih društava (uključujući većinu unutar ‘prosvećene i emancipovane građanske elite’) nije na te tronove iznova popela, ko činjenjem, ko nečinjenjem.

Teofil Pančić, Vreme

– Kako može da postoji mudrost bez milosti?

Više filozofa je verovalo da Bog nije milostiv… Spinoza nije verovao da je Bog milostiv. Rekao je Bog dela prema svojim zakonima. Mislim da je Šestov rekao da postoji neki bog ali da nije dobar. Možda je Bog i milostiv ali, pošto ne mogu to da vidim, nikad ga ne bih nazvao milostivim. Nazvao bih ga Bogom mudrosti, moći. Mislim da je Maltus izrazio ideje koje su sama suština stvarnosti. Ništa što je rečeno posle Maltusa ne može da poništi ono što je on rekao. Ne moram da navodim Maltusa, i sam vidim iste stvari – da glad i bolest, smrt i borba, održavaju svet u ravnoteži. Kada bi u životu ostali svi slonovi koji su stvoreni, i svi lavovi i sve vaške, svemir bi bio pun vašaka, slonova i lavova. Smrt i patnja su deo stvaranja, a s obzirom da ne volim patnju i ne volim da gledam kako se ljudi i životinje bore protiv nečega što je neizbežno, ne mogu da Boga nazovem milostivim, i u sebi osećam veliki protest protiv stvaranja. Iako odgovor možda postoji, nikada se neće pronaći na ovoj zamlji, a s obzirom da ja još uvek jesam na ovoj zemlji, osećam neku vrstu protesta. Mislim da sam vam rekao da, ako bih ikada pokušao da stvorim neku religiju, recimo za sebe, nazvao bih je religijom protesta.

Vidim isto tako da je i čovek nemilosrdan, iako i sam pati i umire, i plaši se raka i srčanog udara i svih drugih stvaril. Onog trena kada dobije malo moći nesreće druih ljudi više mu ništa ne znače. S obzirom da ne vidim milost Božju a vidim čovekovu okrutnost, daleko sam od toga da budem optimista. Jednom sam, za sebe, zapisao neku vrstu rezimea onoga što vidim u svetu. Pisao sam na jidišu i mogu da vam dam samo kratak pregled. Započinje otprilike ovako – i vuk i ovca umiru u bedi ali izgleda da niko ne brine o tome što im se događa. Sam Bog, Gospod, stvorio je svet tako da je u njemu načelo nasilja i ubistva naviše. Sve što mogu da učinim u takvom svetu jeste ne da živim, već da krijumčarim sebe kroz život, da se provlačim kroz ovu džunglu i krijem se, s mojim parčetom hleba, da me zveri i ubice ne bi uhvatile.

– Da li može da postoji bog koji nije milostiv i koji ne brine za čoveka?

Verujem da ta sila nije slepa čak i ako ne verujete u Boga, ipak verujete da postoji priroda. I vuk i ovca postoje, i elektroni i magnetni talasi i sve ostalo. Nije važno da li kažem Priroda ili Bog, verujem da Priroda vidi. priroda koja vidi i misli jeste Bog.

– Ali ako Priroda vidi stvari bez milosti, bez sažaljenja prema čoveku, zašto se vi kao čovek ne pobunite protiv toga, zašto podržavate Boga?

Ne podržavam ga… upravo suprotno. Kažem da protestujem protiv toga. Moj odnos s Bogom je odnos protesta. Ne mogu da se bunim, jer za pobunu je potrebna neka moć, ali za protestovanje vam ne treba nikakva moć. Spinoza je rekao da moramo da se pomirimo s Prirodom, da volimo Boga ili supstanciju intelektualno, ja to ne govorim. Ja kažem da je Bog velik, da je pun mudrosti.

– Kakve mudrosti ako izaziva svu tu patnju?

Da biste stvorili cvet, morate da posedujete mudrost. Bez obzira što će dva sata kasnije neki vo pojesti taj cvet, ipak moramo da se divimo mudrosti u njegovom stvaranju.

– U Mocartu i Betovenu postoji mudrost koja je možda lepša od cveta?

O, ne, nikako… svi profesori na svetu i svi hemičari i svi fizičari ne bi mogli da stvore cvet.

– Ali Božja muzika nije toliko lepa kao čovekova. Muzika Baha, Mocarta i Betovena lepša je od vetra i mora.

Pre svega, Bog je stvorio Baha i Betovena. Oni su takođe deo onoga što je Bog stvorio. Stoga je za panteistu sve Bog. Za mene, Bog i Priroda su jedno isto, izuzev što verujem da je priroda svesna, da zna šta radi i kada bismo to bolje znali, mogli bismo da kažemo da radi pravu stvar, ali pošto to ne znamo i patimo, mi protestujemo. protestom koji ja izražavam ne tvrdi se da je Bog rđav. Ja samo kažem da je on rđav onoliko koliko ja mogu da vidim. Jer da bih znao šta Bog jeste, morao bih da znam sve zvezde i planete, celokupan svemir. Ne možete da napišete prikaz knjige koja ima bilion stranica ako ste pročitali samo jednu stranu. Mogu da kažem jednu stvar – ovoj stranici se divim ali me se ne dopada, s moje tačke gledišta. To što sam vegeterijanac povezano je s tim protestom. čovek koji jede meso ili lovac, slaže se sa okrutnostima prirode, i svakim parčetom mesa ili ribe podržava stav da je u pravu onaj ko ima moć. Vegeterijanstvo je moja religija, moj protest.

– Dakle, svemir je za vas kao beskrajna knjiga.

Beskrajna knjiga od koje sam pročitao samo nekoliko redova. Ti redovi mi izgledaju divni ali okrutni. Najbolje što možemo da učinimo jeste da ćutimo, mada ima trenutaka kada moramo da uzviknemo – zašto mučiš nemoćne? Zašto gradiš svoju slavu na našoj bedi? Ponekad pomislim da je Svemogući umoran od svih pohvala i laskanja kojima ga obasipamo.

– Povremeno vas optužuju da ste mizantrop. Kakva je to mizantropija?

Sastoji se u tome da se ništa ne traži od drugih ljudi, čak ni od prijatelja – novac, počasti, priznanje. U ovoj epohi u kojoj svako moli – ne samo siromašni već i moćni – glasajte za mene, kupujte moje proizvode, podržavajte moju organizaciju, volite me, hvalite me, oprostite zbog mojih zločina – suzdržavanje od tog prosjačenja predstavlja visok ideal. prosjak u torbi često nosi nož. Ja ne pružam ruku ni za kakvu uslugu. Ljubav ne tražim ukoliko sama ne naiđe.

Razgovori sa Isakom Singerom

“To što se dešava sa novinarima dešava se i sa drugim profesijama: državnim službenicima, sudijama, tužiocima i nastavnicima. Kada ljudi dođu kod mene i počnu da se žale na pritiske, često umem da budem i neprijatan jer, gospodo, znamo gde živimo. Prihvatili smo, uključujući i mene, da budemo zaštitnici javnog interesa, jer šta su drugo novinari, profesori, tužioci i sudije. Ukoliko se osećamo sposobnim da radimo posao koga smo se prihvatili, onda moramo da prihvatimo i taj deo naše uloge. Ovde su se ljudi okupili da brane novinarsku profesiju i sve građane koji su se našli u ovakvoj situaciji. Ironično, okupili smo se da branimo državu od države same”.

Saša Janković, zaštitnik građana, na skupu podrške Zoranu Kesiću

Friends:

I am sorry to be the bearer of bad news, but I gave it to you straight last summer when I told you that Donald Trump would be the Republican nominee for president. And now I have even more awful, depressing news for you: Donald J. Trump is going to win in November. This wretched, ignorant, dangerous part-time clown and full time sociopath is going to be our next president. President Trump. Go ahead and say the words, ‘cause you’ll be saying them for the next four years: “PRESIDENT TRUMP.”

Never in my life have I wanted to be proven wrong more than I do right now.

I can see what you’re doing right now. You’re shaking your head wildly – “No, Mike, this won’t happen!” Unfortunately, you are living in a bubble that comes with an adjoining echo chamber where you and your friends are convinced the American people are not going to elect an idiot for president. You alternate between being appalled at him and laughing at him because of his latest crazy comment or his embarrassingly narcissistic stance on everything because everything is about him. And then you listen to Hillary and you behold our very first female president, someone the world respects, someone who is whip-smart and cares about kids, who will continue the Obama legacy because that is what the American people clearly want! Yes! Four more years of this!

You need to exit that bubble right now. You need to stop living in denial and face the truth which you know deep down is very, very real. Trying to soothe yourself with the facts – “77% of the electorate are women, people of color, young adults under 35 and Trump cant win a majority of any of them!” – or logic – “people aren’t going to vote for a buffoon or against their own best interests!” – is your brain’s way of trying to protect you from trauma. Like when you hear a loud noise on the street and you think, “oh, a tire just blew out,” or, “wow, who’s playing with firecrackers?” because you don’t want to think you just heard someone being shot with a gun. It’s the same reason why all the initial news and eyewitness reports on 9/11 said “a small plane accidentally flew into the World Trade Center.” We want to – we need to – hope for the best because, frankly, life is already a shit show and it’s hard enough struggling to get by from paycheck to paycheck. We can’t handle much more bad news. So our mental state goes to default when something scary is actually, truly happening. The first people plowed down by the truck in Nice spent their final moments on earth waving at the driver whom they thought had simply lost control of his truck, trying to tell him that he jumped the curb: “Watch out!,” they shouted. “There are people on the sidewalk!”

Well, folks, this isn’t an accident. It is happening. And if you believe Hillary Clinton is going to beat Trump with facts and smarts and logic, then you obviously missed the past year of 56 primaries and caucuses where 16 Republican candidates tried that and every kitchen sink they could throw at Trump and nothing could stop his juggernaut. As of today, as things stand now, I believe this is going to happen – and in order to deal with it, I need you first to acknowledge it, and then maybe, just maybe, we can find a way out of the mess we’re in.

Don’t get me wrong. I have great hope for the country I live in. Things are better. The left has won the cultural wars. Gays and lesbians can get married. A majority of Americans now take the liberal position on just about every polling question posed to them: Equal pay for women – check. Abortion should be legal – check. Stronger environmental laws – check. More gun control – check. Legalize marijuana – check. A huge shift has taken place – just ask the socialist who won 22 states this year. And there is no doubt in my mind that if people could vote from their couch at home on their X-box or PlayStation, Hillary would win in a landslide.

But that is not how it works in America. People have to leave the house and get in line to vote. And if they live in poor, Black or Hispanic neighborhoods, they not only have a longer line to wait in, everything is being done to literally stop them from casting a ballot. So in most elections it’s hard to get even 50% to turn out to vote. And therein lies the problem for November – who is going to have the most motivated, most inspired voters show up to vote? You know the answer to this question. Who’s the candidate with the most rabid supporters? Whose crazed fans are going to be up at 5 AM on Election Day, kicking ass all day long, all the way until the last polling place has closed, making sure every Tom, Dick and Harry (and Bob and Joe and Billy Bob and Billy Joe and Billy Bob Joe) has cast his ballot? That’s right. That’s the high level of danger we’re in. And don’t fool yourself — no amount of compelling Hillary TV ads, or outfacting him in the debates or Libertarians siphoning votes away from Trump is going to stop his mojo.

Here are the 5 reasons Trump is going to win:

- Midwest Math, or Welcome to Our Rust Belt Brexit. I believe Trump is going to focus much of his attention on the four blue states in the rustbelt of the upper Great Lakes – Michigan, Ohio, Pennsylvania and Wisconsin. Four traditionally Democratic states – but each of them have elected a Republicangovernor since 2010 (only Pennsylvania has now finally elected a Democrat). In the Michigan primary in March, more Michiganders came out to vote for the Republicans (1.32 million) that the Democrats (1.19 million). Trump is ahead of Hillary in the latest polls in Pennsylvania and tied with her in Ohio. Tied? How can the race be this close after everything Trump has said and done? Well maybe it’s because he’s said (correctly) that the Clintons’ support of NAFTA helped to destroy the industrial states of the Upper Midwest. Trump is going to hammer Clinton on this and her support of TPP and other trade policies that have royally screwed the people of these four states. When Trump stood in the shadow of a Ford Motor factory during the Michigan primary, he threatened the corporation that if they did indeed go ahead with their planned closure of that factory and move it to Mexico, he would slap a 35% tariff on any Mexican-built cars shipped back to the United States. It was sweet, sweet music to the ears of the working class of Michigan, and when he tossed in his threat to Apple that he would force them to stop making their iPhones in China and build them here in America, well, hearts swooned and Trump walked away with a big victory that should have gone to the governor next-door, John Kasich.

From Green Bay to Pittsburgh, this, my friends, is the middle of England – broken, depressed, struggling, the smokestacks strewn across the countryside with the carcass of what we use to call the Middle Class. Angry, embittered working (and nonworking) people who were lied to by the trickle-down of Reagan and abandoned by Democrats who still try to talk a good line but are really just looking forward to rub one out with a lobbyist from Goldman Sachs who’ll write them nice big check before leaving the room. What happened in the UK with Brexit is going to happen here. Elmer Gantry shows up looking like Boris Johnson and just says whatever shit he can make up to convince the masses that this is their chance! To stick to ALL of them, all who wrecked their American Dream! And now The Outsider, Donald Trump, has arrived to clean house! You don’t have to agree with him! You don’t even have to like him! He is your personal Molotov cocktail to throw right into the center of the bastards who did this to you! SEND A MESSAGE! TRUMP IS YOUR MESSENGER!

And this is where the math comes in. In 2012, Mitt Romney lost by 64 electoral votes. Add up the electoral votes cast by Michigan, Ohio, Pennsylvania and Wisconsin. It’s 64. All Trump needs to do to win is to carry, as he’s expected to do, the swath of traditional red states from Idaho to Georgia (states that’ll never vote for Hillary Clinton), and then he just needs these four rust belt states. He doesn’t need Florida. He doesn’t need Colorado or Virginia. Just Michigan, Ohio, Pennsylvania and Wisconsin. And that will put him over the top. This is how it will happen in November.

- The Last Stand of the Angry White Man. Our male-dominated, 240-year run of the USA is coming to an end. A woman is about to take over! How did this happen?! On our watch! There were warning signs, but we ignored them. Nixon, the gender traitor, imposing Title IX on us, the rule that said girls in school should get an equal chance at playing sports. Then they let them fly commercial jets. Before we knew it, Beyoncé stormed on the field at this year’s Super Bowl (our game!) with an army of Black Women, fists raised, declaring that our domination was hereby terminated! Oh, the humanity!

That’s a small peek into the mind of the Endangered White Male. There is a sense that the power has slipped out of their hands, that their way of doing things is no longer how things are done. This monster, the “Feminazi,”the thing that as Trump says, “bleeds through her eyes or wherever she bleeds,” has conquered us — and now, after having had to endure eight years of a black man telling us what to do, we’re supposed to just sit back and take eight years of a woman bossing us around? After that it’ll be eight years of the gays in the White House! Then the transgenders! You can see where this is going. By then animals will have been granted human rights and a fuckin’ hamster is going to be running the country. This has to stop!

- The Hillary Problem. Can we speak honestly, just among ourselves? And before we do, let me state, I actually like Hillary – a lot – and I think she has been given a bad rap she doesn’t deserve. But her vote for the Iraq War made me promise her that I would never vote for her again. To date, I haven’t broken that promise. For the sake of preventing a proto-fascist from becoming our commander-in-chief, I’m breaking that promise. I sadly believe Clinton will find a way to get us in some kind of military action. She’s a hawk, to the right of Obama. But Trump’s psycho finger will be on The Button, and that is that. Done and done.

Let’s face it: Our biggest problem here isn’t Trump – it’s Hillary. She is hugely unpopular — nearly 70% of all voters think she is untrustworthy and dishonest. She represents the old way of politics, not really believing in anything other than what can get you elected. That’s why she fights against gays getting married one moment, and the next she’s officiating a gay marriage. Young women are among her biggest detractors, which has to hurt considering it’s the sacrifices and the battles that Hillary and other women of her generation endured so that this younger generation would never have to be told by the Barbara Bushes of the world that they should just shut up and go bake some cookies. But the kids don’t like her, and not a day goes by that a millennial doesn’t tell me they aren’t voting for her. No Democrat, and certainly no independent, is waking up on November 8th excited to run out and vote for Hillary the way they did the day Obama became president or when Bernie was on the primary ballot. The enthusiasm just isn’t there. And because this election is going to come down to just one thing — who drags the most people out of the house and gets them to the polls — Trump right now is in the catbird seat.

- The Depressed Sanders Vote. Stop fretting about Bernie’s supporters not voting for Clinton – we’re voting for Clinton! The polls already show that more Sanders voters will vote for Hillary this year than the number of Hillary primary voters in ’08 who then voted for Obama. This is not the problem. The fire alarm that should be going off is that while the average Bernie backer will drag him/herself to the polls that day to somewhat reluctantly vote for Hillary, it will be what’s called a “depressed vote” – meaning the voter doesn’t bring five people to vote with her. He doesn’t volunteer 10 hours in the month leading up to the election. She never talks in an excited voice when asked why she’s voting for Hillary. A depressed voter. Because, when you’re young, you have zero tolerance for phonies and BS. Returning to the Clinton/Bush era for them is like suddenly having to pay for music, or using MySpace or carrying around one of those big-ass portable phones. They’re not going to vote for Trump; some will vote third party, but many will just stay home. Hillary Clinton is going to have to do something to give them a reason to support her — and picking a moderate, bland-o, middle of the road old white guy as her running mate is not the kind of edgy move that tells millenials that their vote is important to Hillary. Having two women on the ticket – that was an exciting idea. But then Hillary got scared and has decided to play it safe. This is just one example of how she is killing the youth vote.

- The Jesse Ventura Effect. Finally, do not discount the electorate’s ability to be mischievous or underestimate how any millions fancy themselves as closet anarchists once they draw the curtain and are all alone in the voting booth. It’s one of the few places left in society where there are no security cameras, no listening devices, no spouses, no kids, no boss, no cops, there’s not even a friggin’ time limit. You can take as long as you need in there and no one can make you do anything. You can push the button and vote a straight party line, or you can write in Mickey Mouse and Donald Duck. There are no rules. And because of that, and the anger that so many have toward a broken political system, millions are going to vote for Trump not because they agree with him, not because they like his bigotry or ego, but just because they can.Just because it will upset the apple cart and make mommy and daddy mad. And in the same way like when you’re standing on the edge of Niagara Falls and your mind wonders for a moment what would that feel like to go over that thing, a lot of people are going to love being in the position of puppetmaster and plunking down for Trump just to see what that might look like. Remember back in the ‘90s when the people of Minnesota elected a professional wrestler as their governor? They didn’t do this because they’re stupid or thought that Jesse Ventura was some sort of statesman or political intellectual. They did so just because they could. Minnesota is one of the smartest states in the country. It is also filled with people who have a dark sense of humor — and voting for Ventura was their version of a good practical joke on a sick political system. This is going to happen again with Trump.

Coming back to the hotel after appearing on Bill Maher’s Republican Convention special this week on HBO, a man stopped me. “Mike,” he said, “we have to vote for Trump. We HAVE to shake things up.” That was it. That was enough for him. To “shake things up.” President Trump would indeed do just that, and a good chunk of the electorate would like to sit in the bleachers and watch that reality show.

Michael Moore

A masterpiece about Sicily, meditation on eternity, and an endlessly rich historical tapestry, meticulously composed in color and on 70 mm. Luchino Visconti based the picture on the Count Giuseppe Tomasi di Lampedusa’s posthumously published novel, about a Sicilian prince at the time of the Italian unification, or Risorgimento, who steps away from power and influence because he realizes that the life he and his family have led is coming to an end, that he has to get out of the way for younger and more ambitious men like his nephew Tancredi. Visconti and his fellow screenwriters (there were four of them, including his frequent collaborators Suso Cecchi D’Amico and Enrico Medioli) took Lampedusa’s novel and fashioned a whole new work on a grand scale, an epic but of a very unusual type. Time itself is the protagonist of The Leopard: the cosmic scale of time, of centuries and epochs, on which the prince muses; Sicilian time, in which days and nights stretch to infinity; and aristocratic time, in which nothing is ever rushed and everything happens just as it should happen, as it has always happened. The landscapes, the extraordinary settings with their painstakingly selected objects and designs, the costumes, the ceremonies and rituals—it’s all at the service of deepening our sense of time and large-scale change, and the entire picture culminates in an hour-long sequence at a ball in which you can feel, through the eyes of the prince, an entire way of life (one that Visconti himself knew quite well) in the process of fading away. Like Contempt, The Leopard was initially overshadowed by the circumstances around it, namely, the casting of Burt Lancaster as the prince. Here in America, we saw the picture in a shortened and dubbed version (Lancaster was speaking English) that was a little unsatisfying: you could clearly see that the movie Visconti had intended wasn’t quite all there, and it was jarring to watch Lancaster speaking in his normal voice surrounded by Alain Delon and Claudia Cardinale and Paolo Stoppa dubbed into American English. When I got to see the whole thing, I was astonished by the picture and by Lancaster, who gives all of himself to the role and to the world of the film. Visconti had wanted Laurence Olivier, and he was initially very curt with Lancaster, but the actor won him over and they became lifelong friends. I could go on and on about The Leopard. It’s a film that has become more and more important to me as the years have gone by.

Martin Scorsese

Dok pišem, visoko civilizovani ljudi lete nebom iznad mene sa namerom da me ubiju. Nemaju oni ništa protiv mene kao pojedinca, ne osećaju nikakvo neprijateljstvo, a ni ja protiv njih. Oni samo obavljaju svoju dužnost, kako se to lepo kaže. Većinom su to, zasigurno, miroljubivi ljudi dobra srca kojima nikad u njihovom privatnom životu ne bi palo napamet da nekog ubiju. S druge pak strane, ako nekom od njih uspe da me raznese bombom u komadiće on zbog toga neće izgubiti miran san. U službi domovini svi su gresi oprošteni.

Džordž Orvel, Lav i jednorog

Moj sin nije upisao fakultet i sada će da postane radnik. Ništa ne pada sa neba, nadam se da će on postati radnik i da će moći sve sam sebi da obezbedi. Ponosan sam na to što će biti radnik, jer u tome nema sramote.

Aleksandar Vučić

Moj sin Marko sve što je uradio u životu uradio je sopstvenim rukama. Od 16 godina se zaposlio u Požarevcu jer nije mogao da izdrži da bude ovde sin predsednika Republike i medijske pritiske. Otišao je tamo u naš rodni grad, zaposlio se, znate šta da radi, da nosi gajbe s praznim i punim flašama za jednu kafanu za 5000 dinara mesečno, jer je takav čovek, jer je želeo uvek da bude samostalan.

Slobodan Milošević