The first world war in German art: Otto Dix’s first-hand visions of horror

In 1924 the German artist and war veteran Otto Dix looked back at the first world war on its 10th anniversary, just as we are doing on its 100th. What did he see? Today there is a fashion, in Britain, to celebrate the heroism of our grandfathers and their hard-won victory of 1914-1918. It’s as if the clock is being turned back and the propaganda of the war believed all over again. Even the German war guilt clause written by the victors into the Treaty of Versailles in 1919 has been turned into “fact” – after all, who wants to trawl through the complex causes of this conflict and face the depressing truth that it ultimately happened because no one in July 1914 understood how destructive a modern industrial war could be?

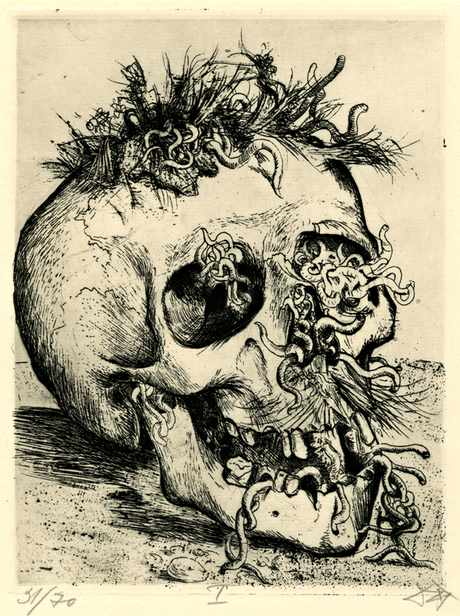

We need to shake off the nostalgia of a centenary’s forgetful pomp and look at the first world war through fresh eyes – German eyes. For no other artists saw this dreadful war as clearly as German artists did. While British war artists, for example, were portraying the generals, Germans saw the skull in no man’s land.

Der Krieg, the series of prints Otto Dix published in 1924, and which is about to go on view at the De La Warr Pavilion in Bexhill-on-Sea, is a startling vision of the apocalypse that really happened on Europe’s soil 100 years ago.

A German soldier sits in a trench, resting against its muddy wall. He is smiling, but the grin is empty and hollow-eyed – for his face is a bare skull. He has been dead a while. No one bothered to bury him. His helmet is still on his skull, and his boots reveal a rotting ankle. In another print, a severed skull lies on the earth. Grass has grown on its crown. More grass resembles a moustache under its nose. Out of the eyes, vegetation bursts. Worms crawl sickeningly out of a gaping mouth.

Dix had seen these things as a frontline soldier. At the time, he later confessed, he did not think about them too much. It was after he went home that the nightmares started. In what might now be called post-traumatic stress, he kept seeing the horrors of the trenches. He was compelled to show them, with nothing held back.

The prints gathered in Der Krieg (The War) are just part of the hideous outpouring of images he unleashed. It was as if Dix needed to vomit his memories in order to purge himself of all that haunted him. He engraved these black-and-white vignettes just after painting The Trench, a horrific masterpiece that distilled the western front into one grisly carnival of death. The painting was hugely controversial, and in 1937 the Nazis included it in the notorious Degenerate Artexhibition that vilified modern German artists like Dix. The confiscated painting vanished during the second world war, perhaps burned in the bombing of Dresden.

Even with that loss, Dix’s war art is a gut-wrenching act of witness. Yet he was not alone. He was part of a radical art movement that rejected the conflict and the European civilisation reponsible for it.

It was not at all obvious that a man such as Dix would create some of the defining pacifist images of the 20th century. In 1914 he was a fierce German patriot who joined up enthusiastically. He became a machine gunner and fought at the Battle of the Somme, efficiently mowing down British troops. He won the Iron Cross (second class) and began training to be a pilot. How did this courageous soldier turn into an anti-war artist?

To understand that, we need to comprehend that, during the first world war, a radical minority of Germans turned to artistic and political revolution, rather than nationalism. Like the British war poets, Germany’s young artists came to hate the war, but unlike the poets, they organised to resist it.

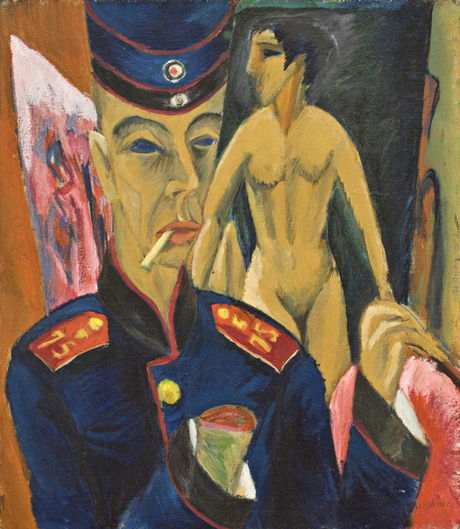

Many simply could not take the front. Like Dix, the brilliant expressionist painter Ernst Ludwig Kirchner joined up in 1914, but his mental health soon collapsed. In his 1915 painting Self-Portrait as a Soldier (currently in the National Portrait Gallery’s exhibition The Great War in Portraits), he gives visual form to shell shock. The painter stands in uniform, his face yellow and eyes dazed, lurching like a sleepwalker, his right hand severed at the wrist.

Kirchner had not really lost a hand. The bloody stump he waves is an image of artistic and sexual despair – war has unmanned him. Kirchner’s pre-war paintings were sensual primeval nudes, but in his 1915 self-portrait he has turned helplessly from a naked model. It is not only a hand that has been amputated, but his very life force.

Like Dix and Kirchner, the poet Hugo Ball wanted to fight. He failed the medical three times. Visiting Belgium so he could at least see the front, he was so shocked that he turned against war, fled to Switzerland with his girlfriend, cabaret singer Emmy Hennings, and in 1916 founded the Cabaret Voltaire in Zurich. This was the birthplace of Dada, the most extreme art movement of the 20th century, which used nonsense, noise, cut-ups and chaos to repudiate war. “The beginning of Dada was really a reaction against mass murder in Europe,” said Ball.

Dada was the counter-culture of the first world war, just as psychedelia was to be the counter-culture of Vietnam. At a time when supposedly rational decisions sent so many to their deaths – in 1916, the year Dada began, General Haig ordered an advance at the Somme that killed 19,000 British soldiers on a single day – Dada feigned madness. Its angriest practitioners were Germans.

Helmut Herzfeld wasn’t so sure he wanted to be German, however. In 1916 he got so sick of the war’s relentless propaganda that he changed his name to John Heartfield – a shockingly subversive adoption of the enemy’s language. He got out of the army by pretending to be mad, and then, sent to work as a postman, threw away the mail to hinder Germany’s war effort.

In 1919, at the First International Dada Art Fair in Berlin, Heartfield and another Dadaist, Rudolf Schlichter, hung a dummy of a German officer with a pig’s face from the ceiling. It is impossible to think of Britain’s generals being portrayed like this – but then Germany had lost, and Berlin was riven by revolution.

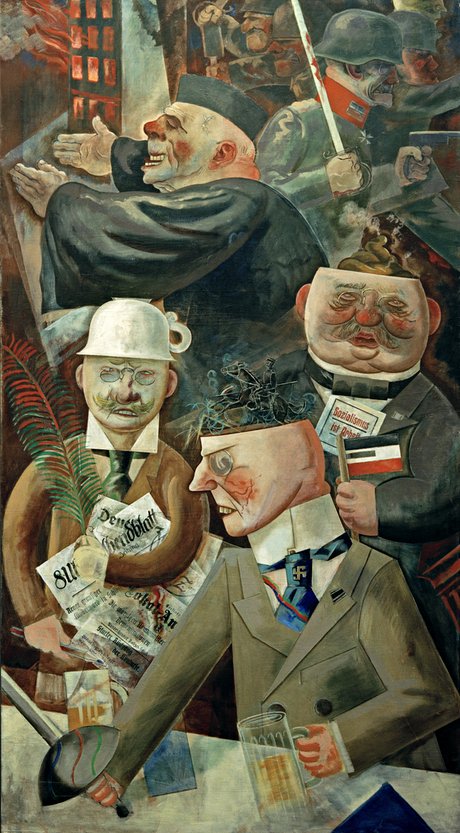

Dix also exhibited at the Dada fair. He got involved with this revolutionary movement after meeting its most charismatic exponent, George Grosz (much like Heartfield, he adopted the English “George” as a war protest). While Dix was at the front, Grosz was sending soldiers Dadaist “care packages” full of satirically useless stuff like neatly ironed white shirts.

At the 1919 fair Dix exhibited a painting of maimed war veterans begging on a Berlin pavement. The city was full of damaged men. In another of his Dada paintings, Card-Playing War Cripples, men breathe through tubes and use feet to hold cards – they are no longer men, they are collages.

For it took a new art to do justice to the Great War. So Dada invented photomontage, a shattered mirror of the violence done to bodies by war. At the Dada fair in Berlin this was made explicit when, over the broken bodies painted by Dix, a photomontage by Grosz of a man who seems horribly disfigured was inserted. This ruined face resembles photographs of the war’s victims – until you realise the “Victim of Society” is nothing but an Arcimboldo head made of cut-out newspaper pictures.

German artists showed the war with utter clarity when others turned away. While the Dadaists were cutting up society, the war veteran Max Beckmann painted his grotesque vision of a world gone mad, Die Nacht (The Night). Yet their warnings went unheeded. In 1924 Dix’s war engravings were shown in an anti-war exhibition. In less than a decade he would be living in internal exile, a banned “degenerate artist”, while leaders with very different memories of the first world war laid the foundations of the second.

The truth survives. In his 1924 drawing How I Looked as a Soldier, Dix portrays himself holding his machine gun. He’s unshaven under his helmet and his eyes are narrow slits. Dix the truth-teller looks back at Dix the killing machine.